NBP: 8% fall in two days

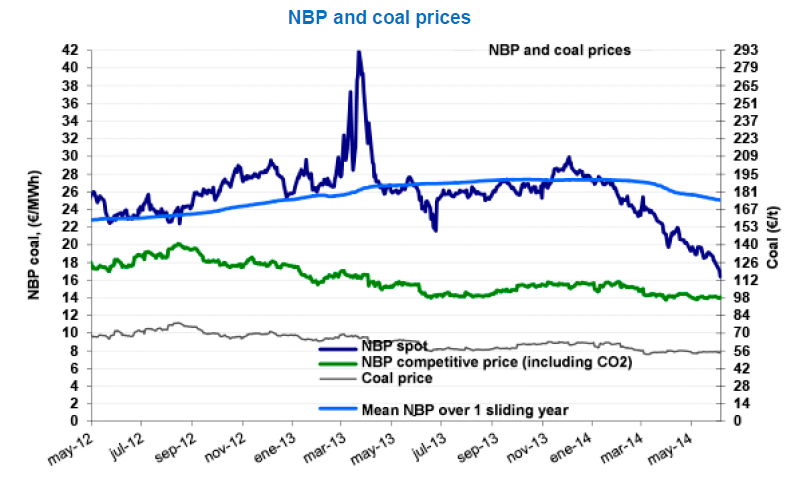

The fall in the price of NBP which began in December (-45%!) is continuing (an 8% fall in May compared with the previous month) and even picked up the pace in June: an 8% fall between 30 May and the current €16.4/MWh (US$6.5/MBtu) listings. This means that the price of NBP is approaching the competitive price for coal – an estimated €14/MWh (US$5.6/MBtu) based on a level of €55/tonne for coal (€61/tonne in 2013) and €5.4/tonne for CO2. This price correction can be attributed to several factors, including the extension granted until 10 June to find an agreement on the Ukrainian crisis, but mainly to the UK market context. Demand is moderate (71 Gm3 over a

The fall in the price of NBP which began in December (-45%!) is continuing (an 8% fall in May compared with the previous month) and even picked up the pace in June: an 8% fall between 30 May and the current €16.4/MWh (US$6.5/MBtu) listings. This means that the price of NBP is approaching the competitive price for coal – an estimated €14/MWh (US$5.6/MBtu) based on a level of €55/tonne for coal (€61/tonne in 2013) and €5.4/tonne for CO2. This price correction can be attributed to several factors, including the extension granted until 10 June to find an agreement on the Ukrainian crisis, but mainly to the UK market context. Demand is moderate (71 Gm3 over a  sliding year as opposed to 80 Gm3 12 months ago), temperatures are rising, stocks are high as they are on the continent, and sales of LNG have been sustained since the end of March (40/50 mcmd – 20/25% of demand). Overall, the LNG market is unaffected by tensions, with prices in Asia of under US$13/MBtu, as opposed to US$20 in February. The shoring up of Norwegian deliveries at the end of May via the “Langeled” gas pipeline should also be mentioned among the economic factors. The imminent closure for maintenance (11 to 26 June) of the Interconnector, which is currently used to transit 30 mcmd to the continent, is also a factor pushing prices down (down to €14/MWh, or US$5.6/MBtu?). And the downward trend of oil price indexation in contracts (which encourages spot gas prices to respond in a more marked way to supply/demand balance) should also be highlighted. This is a structural movement in Europe (ENI/Gazprom agreement in May based on the market, 60% of spot prices referenced in France) that is in the process of affecting Asia.

sliding year as opposed to 80 Gm3 12 months ago), temperatures are rising, stocks are high as they are on the continent, and sales of LNG have been sustained since the end of March (40/50 mcmd – 20/25% of demand). Overall, the LNG market is unaffected by tensions, with prices in Asia of under US$13/MBtu, as opposed to US$20 in February. The shoring up of Norwegian deliveries at the end of May via the “Langeled” gas pipeline should also be mentioned among the economic factors. The imminent closure for maintenance (11 to 26 June) of the Interconnector, which is currently used to transit 30 mcmd to the continent, is also a factor pushing prices down (down to €14/MWh, or US$5.6/MBtu?). And the downward trend of oil price indexation in contracts (which encourages spot gas prices to respond in a more marked way to supply/demand balance) should also be highlighted. This is a structural movement in Europe (ENI/Gazprom agreement in May based on the market, 60% of spot prices referenced in France) that is in the process of affecting Asia.